Major moss role revealed

A new study spells out the global importance of moss - an often ignored or even removed form of plant life.

A new study spells out the global importance of moss - an often ignored or even removed form of plant life.

Mosses, often seen as a nuisance in gardens and urban spaces, are actually playing a vital role in protecting the health of the planet, according to a new study led by researchers at UNSW Sydney.

Mosses, the ancient ancestors of all plants, are not only essential for green spaces, but are also significant for the health of the entire planet when they grow on topsoil.

They may even have an important role in mitigating climate change by capturing large amounts of carbon.

The study, published in the journal Nature Geoscience, involved over 50 researchers from international research institutions who collected samples of mosses growing on soil from more than 123 ecosystems across the globe, including lush tropical rainforests, barren polar landscapes, and arid deserts.

The researchers found that mosses cover a staggering 9.4 million km2 in the environments surveyed, which is equivalent in size to Canada or China.

The lead author of the study, Dr David Eldridge, explained that the researchers were interested in understanding how natural systems of native vegetation that have not been disturbed much differ from human-made systems like parks and gardens.

They wanted to look at the role of mosses in providing essential services to the environment and were surprised to find that mosses were doing an array of amazing things.

The researchers assessed 24 ways that moss provided benefits to soil and other plants, and showed that mosses are the lifeblood of plant ecosystems, laying the foundations for plants to flourish in ecosystems around the world.

In patches of soil where mosses were present, there was more nutrient cycling, decomposition of organic matter, and even control of pathogens harmful to other plants and people.

Furthermore, the authors of the study suggest that mosses may play an important role in reabsorbing carbon dioxide.

They estimate that compared to bare soils with no moss, this ancient precursor to plants supports the storage of 6.43 gigatonnes – or 6,430,000,000 tonnes – of carbon from the atmosphere.

These levels of carbon capture are of a similar magnitude of levels of carbon release from agricultural practices such as land clearing and overgrazing.

The positive ecological functions of soil mosses are also likely associated with their influence on surface microclimates, such as affecting soil temperature and moisture.

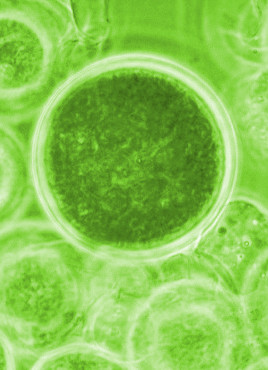

Mosses are different from vascular plants. They have roots and leaves, but their roots are different, with root-like growths called rhizoids that anchor them to the soil surface.

Mosses do not have the plumbing that ordinary plants have, called a xylem and a phloem, which water moves through. Instead, they survive by picking up water from the atmosphere. Some mosses, like the ones in the dry parts of Australia, curl when they get dry, but they do not die – they can live in suspended animation for almost indefinite periods. Researchers have taken mosses out of a packet after 100 years, squirted them with water, and watched them come to life. Their cells do not disintegrate like ordinary plants do.

When moss is lost through land clearing or natural disturbances, it becomes difficult to hold the soil together, leading to erosion.

Dr Eldridge points to research examining the area around the Mount St Helens Volcano following a devastating eruption in the early 1980s. Most of the flora and fauna were denuded near the eruption site, but researchers who tracked how life returned to the mountain noticed that mosses were among the first forms of life to reappear. Mosses were the first to come back because they help to prime the soil for the return of trees, shrubs, and grasses.

Print

Print