Hospital cuts could save lives

Experts say decarbonising the health sector could save thousands of lives.

Experts say decarbonising the health sector could save thousands of lives.

New research suggests methods to reduce the carbon emissions of the Australian health sector by 2040 may avert an estimated 77,000 temperature-related deaths.

The researchers team used computer modelling simulations to estimate the effect of decarbonisation of the health sector and economy of Australia on deaths and the monetary-equivalent welfare gain.

With the Australian health sector responsible for 7 per cent of the nation’s greenhouse gas emissions, the benefits and costs of various decarbonisation trajectories are currently being investigated.

Assuming a low discount rate and high global emissions trajectory, the experts estimate a monetary equivalent welfare gain of $151 billion if the Australian health sector decarbonises by 2040, only accounting for the benefits in reducing temperature-related mortality.

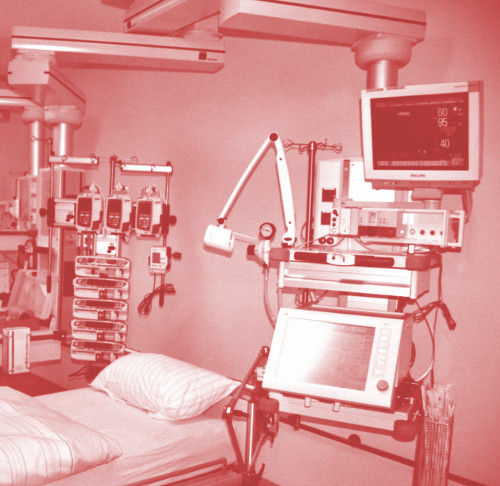

Around two-thirds of Australian healthcare’s carbon footprint comes in the form of brightly lit, always-running hospitals - including the extensive use of heating and cooling technologies, as well as sterilisation and the operation of energy-hungry equipment like MRI machines and other devices. The pharmaceutical drug-manufacturing industry has high emissions too.

The study is accessible here.

Dr Kate Charlesworth, a public health physician who works with the Climate Council, has been envisaging a low-carbon-cost healthcare system.

“Everyone thinks that low-carbon healthcare must be about having solar panels on hospital roofs,” Dr Charlesworth says.

Switching to renewable electricity is an easy win, with hospitals such as the new Royal Adelaide Hospital also installing systems to capture waste heat and using temperature sensors to make facilities more energy efficient.

But the potential cuts extend further than just power sources. Enhancing public health and community services so that people do not wind up in hospital in the first place helps reduce the carbon footprint, as well as reducing low-value care which may be harmful or risky for patients and could see them stuck in hospital longer.

In a separate study, Dr Charlesworth’s team estimated that cutting down on needless pathology tests and excessive imaging requests could save Australia’s health system around 8,000 metric kilotonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent emissions per year.

Other approaches include decarbonising medical procedures, practices and products by finding alternatives where possible.

For example, carbon-costly anaesthetic gases could be swapped for intravenous drugs or less potent anaesthetic gases. Additionally, using telehealth where appropriate can curb travel-related emissions too.

“We need to educate and engage a whole system of health professionals in carbon costs so we can provide the best care to patients while being cognisant of that impact on the planet and the environment,” says Dr Charlesworth.

“Because, ultimately, human health depends on a healthy environment.”

Print

Print