Cat bug cut off

Australian researchers say a parasite from cats may actually change a person’s brain.

Australian researchers say a parasite from cats may actually change a person’s brain.

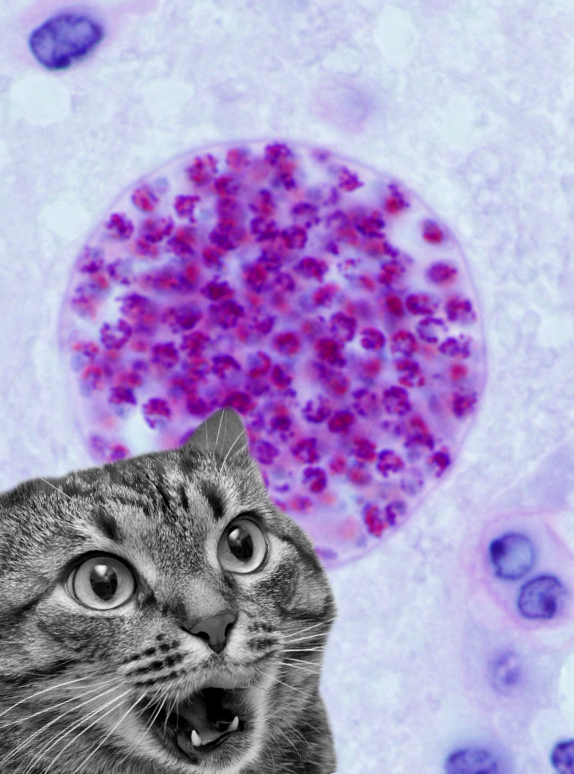

A team at the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research (WEHI) has discovered how the parasite Toxoplasma hijacks host cells and stockpiles food, allowing it to live in a dormant state for years at a time.

Toxoplasma is a common parasite transmitted by cats and found in raw meat, which infects about 30 per cent of the population.

Toxoplasma requires a human host cell – such as a brain cell (neuron) – to live in.

“Toxoplasma infection leads to massive changes in the host cell to prevent immune attack and enable it to acquire a steady nutrient supply,” WEHI researcher Dr Chris Tonkin said.

“The parasite achieves this by sending proteins into the host cell that manipulate the host’s own cellular pathways, enabling it to grow and reproduce.”

Fellow researcher Dr Justin Boddey said some of these proteins might even influence the behaviour of the host.

“There is a fascinating association between Toxoplasma infection and psychiatric diseases including schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. It is now possible to test whether proteins sent from the hibernating parasite into a host neuron disrupt normal brain function and contribute to development of these diseases,” he said.

Once Toxoplasma parasites establish infection, they can lie dormant in the body for the rest of a person’s life.

In people with suppressed immune systems, such as cancer patients, the parasite can reactivate and cause neurological damage and even death.

Dr Tonkin said the teams had identified pathways that allow the parasite to establish chronic infections, unveiling potential avenues for treatment that clear the dormant parasite.

“We discovered that, similar to animals preparing for hibernation, Toxoplasma parasites stockpile large amounts of starch when they become dormant,” he said.

“By identifying and disabling the switch that drives starch storage, we found that we could kill the dormant parasites, preventing them from establishing a chronic infection.”

Dr Tonkin said the finding could lead to a drug to clear chronic Toxoplasma infections, or even a vaccine to prevent infection in at-risk people, such as pregnant women.

“Cats are one of the primary transmitters of Toxoplasma parasites,” Dr Tonkin said.

“If the parasites are transmitted to pregnant women, for example through contact with kitty litter, there is a substantial risk of miscarriage or birth defects.

“We hope to use our discoveries to develop a vaccine that stops cats transmitting the parasite, to prevent these potentially catastrophic consequences.”

Dr Boddey said it had long been a mystery how the Toxoplasma parasite transported proteins into the host.

“Our study showed that the parasite includes a signature on the exported proteins that ‘earmark’ them for transport into the host cell,” he said.

“Blocking transport makes the parasite much less dangerous in infection models, suggesting this may also be a new way of treating Toxoplasma infections.”

The findings will be published in the journal Cell Host & Microbe.

Print

Print