Fossil fuels' environmental knock-out in two rounds found

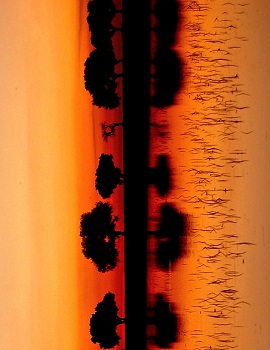

A new Australian study has shown there is more than one way that fossil-fuel extraction damages the land when it is mined.

A new Australian study has shown there is more than one way that fossil-fuel extraction damages the land when it is mined.

Surveys of some of the Earth’s most biologically-diverse regions shows there is a distinct double effect from fossil-fuel extraction, which is threatening the future of northern South America and the western Pacific Ocean

“This double whammy includes the obvious, direct impacts and the more subtle – but often more damaging – indirect impacts,” said Professor Hugh Possingham and Dr Nathalie Butt of the ARC Centre of Excellence for Environmental Decisions (CEED) and The University of Queensland (UQ).

The two areas in focus were studied due to their high biodiversity and large fossil fuel reserves.

“The impacts of fossil fuel extraction on biodiversity have been underestimated because it is assumed that extraction sites have a small footprint relative to other human impacts, such as agriculture,” Professor Possingham said.

With oil demand projected to rise by over 30 per cent, natural gas by 53 per cent and coal by 50 per cent by 2035, researchers warn that the world will lose a lot more of its dwindling wildlife if there are no solid environmental protections on all regions.

The direct impacts of fossil fuel extraction are well-known, including; noise disturbance, pollution, destruction and fragmentation – splitting up forests or landscapes into chunks too small to sustain wildlife populations.

Dr Butt says beyond the direct impacts, the negative effects continue for decades.

“Fossil fuel companies can try to return the area to its ‘original state', but there are indirect impacts that continue long after the extraction, including the introduction of invasive species, soil erosion, water pollution and illegal hunting,” Dr Butt said

“These indirect effects, caused largely by road and pipeline construction, can be far more damaging, and can extend for many kilometres from the mine or well... they can be caused by even small scale extraction, and because they're often off-site, the damage is usually done by the time we can measure it.

“It is critical that international environmental organisations play an active role in ensuring that the extraction takes place according to best practice, ideally avoids areas of high biodiversity and that the trade-offs between biodiversity and development have been considered carefully at a global scale.”

Professor Possingham said: “Before operations start, companies, scientists and local communities need to develop firm plans for different scenarios, such as determining a point when extraction should cease immediately, when mining companies should be fined, or when to start rehabilitating an area.

“Due to increasing worldwide demand for fossil fuels, extraction is going to be an unstoppable force. Recognising the 'double whammy' – direct and indirect threats to biodiversity from fossil fuel extraction – and identifying unfortunate overlaps, is essential in minimising the environmental damage.”

The study “Biodiversity risks from fossil fuel extraction” has been published in the latest issue of Science.

Print

Print