Fishing gear loss studied

CSIRO has published the first ever estimate of commercial fishing gear lost in the world’s oceans.

CSIRO has published the first ever estimate of commercial fishing gear lost in the world’s oceans.

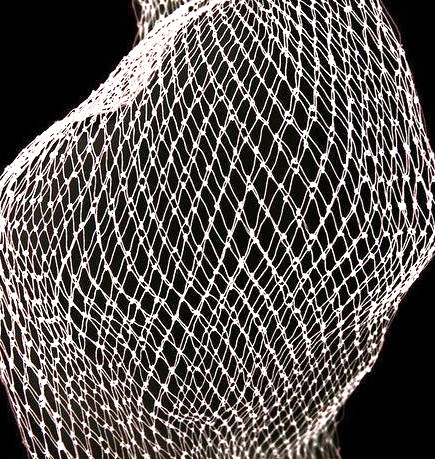

Abandoned, lost or otherwise discarded fishing gear or ‘ghost gear’ contributes substantially to global marine pollution responsible for wide-reaching environmental and socioeconomic impacts.

Until now there has not been a clear global picture of the quantity and type of fishing gear lost worldwide.

Using data from 68 studies published between 1975 and 2017, researchers have produced the first global estimate of commercial fishing gear losses in our oceans.

“The study estimates that 6 per cent of all fishing nets, 9 per cent of all traps, and 29 per cent of all lines are lost or discarded into our oceans each year,” explains Kelsey Richardson, a PhD student from CSIRO’s Marine Debris Team, who led the study.

“The type of fishing gear used, along with how and where it is used, can all influence gear loss by fishers.

“We found that bad weather, gear becoming ensnared on the seafloor, and gear interfering with other gear types are the most common reasons for commercial fishing gear being lost.”

When fishing gear becomes marine pollution, it has significant consequences for marine life and habitats and can be a navigation hazard.

Fishing gear can take hundreds of years to breakdown.

The study, published in Fish and Fisheries, also found that reporting of commercial fishing gear lost at sea has increased through time.

This is most likely due to improved reporting procedures and increases in the number of studies on gear loss across geographic areas and fisheries.

“These new global estimates on fishing gear losses fill a critical knowledge gap. By understanding where and why gear is lost, we can help target interventions to reduce fishing gear ending up in our oceans,” says Dr Denise Hardesty, Principal Research Scientist with CSIRO’s Oceans and Atmosphere.

“When fishers lose gear at sea, they are not only adding to plastic pollution, but affecting their livelihoods.

“An estimated 40.3 million people are employed in fisheries globally and the costs of replacing gear can add up quickly.

“Reducing the amount that ends up in the oceans is good for industry, good for the environment, and good for global food security.”

Print

Print